Who are the Jesuits, exactly? ( Mar 19th 2013, 13:24 by E.H.)

THE election of Pope Francis on March 13th was surprising for several reasons. He is the first pope from South America, making him the first non-European since the 8th century. He is also the only pope to take the name Francis—evoking the humility of St Francis of Assisi, a 12th century Italian monk. Most surprising of all, he is the only member of the Society of Jesus, a religious order dating from the 16th century, to become a pope. But just who are the Jesuits, exactly?

Within the Roman Catholic church, there are two types of priests: the secular clergy and those who are part of religious orders. The first group are known as diocesan priests, and will often (though not always) be attached to a parish and are accountable to a local bishop. They train at a seminary, a theological college, and do not take vows of poverty or seclude themselves from the outside world. In many ways they are the public face of the Catholic church. Religious orders, by contrast, have more autonomy from the central church. They are not under the jurisdiction of a bishop (who in turn has been appointed by the pope) and can live completely excluded from secular society, depending on the order they belong to. Monks and friars—such as the Dominicans, Benedictines, Cistercians (including Trappists) and Franciscans—live within their orders, though often will be connected to educational institutions and can run select parishes. In Britain alone the Benedictines teach at Ampleforth College, a public school in north England, while the Dominicans run Blackfriars Hall, an Oxford college.

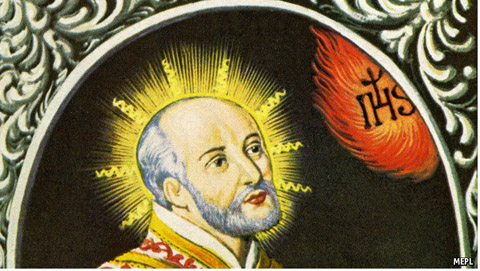

The Society of Jesus is another such religious order. Set up by Ignatius Loyola, a Spanish former soldier, in 1540, there are now over 12,000 Jesuit priests, and the society is one of the largest groups in the Roman Catholic church. Known as the "soldiers of Christ" after the military bearing of their founder (who discovered his vocation, it is claimed, after reading a book on the lives of the saints in a hospital when recovering from war wounds) the order emphasises education, particularly their belief in the importance of learning languages, and the need for missionary evangelism in the life of a priest. They work in churches within cities and towns or run schools and colleges. Unlike diocesan priests, who can complete their studies in four or five years, Jesuits train for 12 years and only become ordained when they are in their thirties. Associated with the more liberal aspects of catholicism, they are less likely than other groups, such as the Oratorians, to conduct mass in the old rite Latin form. On becoming a Jesuit, they also vow never to take ecclesiastical office, such as a bishopric, unless ordered to by the pope.

This last vow is one of the reasons why Pope Francis's election was particularly surprising. According to Brendan Callaghan, the master of Campion Hall, a Jesuit college in Oxford, many Jesuits thought they would never see one of their own in papal office, even if some, such as Pope Francis, had become archbishops. Accustomed to being slightly on the margins of church hierarchy, the Jesuits are marked out by a questioning and occasionally defiant attitude towards the central office of the church. Putting such a potential outsider at the head of an institution mired by difficulties and facing a declining membership is a bold move. It already signals the changes to come.