Early memories of Hong Kong

They called it "a borrowed place within a borrowed time." And that was how we all felt about Hong Kong growing up there years ago. My parents never dreamt of living, not to mention raising a family there. It was all an accident or, rather, the result of collective bad karma. Who was not affected by WWII or the holocaust living in Europe in the thirties and early forties? China had her own holocausts. The one that touched my family most directly was the communist occupation of China in 1949. In the next few years, close to two million Chinese fled to the small island of Hong Kong in a huge exodus, leaving behind their homes, properties and life-long possessions. Hong Kong was then a British colony, with no more than a handful of fishing villages, struggling to become a town. It was partially ceded and partially leased to the British after China's defeat in the Opium War. And so, at the infinite crossroads of space and time, that was where I was later conceived, and where I spent my childhood and early adult years. Mom and Dad never tired of telling us how beautiful their native hometown was, and how idyllic life was in China before the War and the communists. China was our physical and cultural home. The plan was to move us all back there one day. But for us children growing up on the other side of the bamboo curtain, China remained distant and mysterious. A place so near, and yet so far. In the meantime, Hong Kong was home. It was all we really knew.

In no time, the population mushroomed. Hong Kong was throbbing with life. It was a place where the East met the West, where the old and the new congregated. Over a few decades, it became more and more prosperous and westernized, more and more the international city it is today. Although I left Hong Kong for Canada in my early twenties, all my deepest memories of the place are from my childhood and early adolescent years. Like the smell of old pyjamas from a weathered family suitcase, the sensations are vividly familiar and faintly remote at the same time. They are a dormant but colourful part of my inner landscape.

I was the only girl in my family, with three older brothers: daigoh, big brother [John余蔚廷 ('65)], and yigoh, second older brother [Marcus余蔚文('67)], and samgoh, third older brother[Louis余蔚琪('67)]. Being the youngest, I could not call any of my brothers by their names. We were taught to show respect to those older than we were. And they were supposed to do their best to set good examples and to take care of us. As a child, because we moved quite a few times before I was nine, I did not make many early childhood friends. I grew up like a tomboy, tagging along with my brothers. During fun times and on weekends, we would play soccer with little plastic balls, something that only boys did in those days. But I was only allowed to be the goalie. We would play marbles on circles drawn on the floor, or collect sheets of our favorite comic strip characters and their stories. We cut up the little rectangular sheets, each with its own characters and story, and played games with them. We also climbed trees in our neighborhood, or roamed the dirty beaches in our area. We loved to turn over every stone on the beach to look for the tiny crabs hidden beneath them. Often, we caught worms and a dark grayish-looking crawly thing instead. Daigoh called them water cockroaches. We would put them through our fish hooks and spent a whole afternoon fishing by the shore with these living baits.

Other times, we would climb the trees in the deserted hill behind our place, looking for cicadas. We also loved to chase after huge dragonflies, or trap grasshoppers and crickets in the bushes. Daigoh and yigoh knew how to make dried bamboo-leaf pockets to house the crickets. They made an attractive "cr e e k.....cr e e k.....cr e e k......." sound around our place. The male crickets that chirped the loudest were usually great fighters. My brothers would go cricket-fighting with some boys who lived in the neighborhood, or their friends at school. It was so exciting watching them. One time, a teacher told Mom that daigoh was caught peering into his desk at school during a test. They thought he was cheating. Instead they found him totally absorbed, watching a cricket fight inside his drawer.

Sometimes, after a period of heavy rain, we could discover some tadpoles swimming in the puddles at the foot of the hill. We would collect them in jars and bring them home. Watching them grow bigger every day, their tails shrinking and their legs extending until they all turned into little frogs, we were stunned by the transformation and simply overjoyed. The same with silkworms. We used to grow silkworms in big tin cans, and feed them with mulberry leaves in the summer. It was quite a thrill to watch them spin their silk. It was still more exciting to see them eat their way out of their cocoons, and emerge as chubby, feathery moths, ready to mate and to lay eggs again.

Those were the magical moments of childhood. Even though we grew up in a city, Hong Kong in the fifties and early sixties was hardly the industrial and commercial urban centre that we know today. We were exposed to little living things in Nature right in the city that kids today rarely see. We had few toys to play with then. But we made our own. We learned to make kites and paper lanterns from scratch, using rice paper and bamboo sticks that we had cut and stripped thin. All the time, I was an enthusiastic participator, holding the paper and sticks in place and watching keenly while my brothers did the cutting and gluing. Compared with kids nowadays who have expensive and sophisticated toys, who grow up watching TV and playing with computer games, we would seem to be very much deprived. But I am quite happy with this part of my childhood. We had to be more inventive. We interacted more among ourselves and with other kids. And we were protected from violent and stressful images. Our daily lives were also less packed and programmed. We had less but our playtime was creative and spontaneous.

When I was about ten, I had a close friend, Tsui Kit-ming. She and her family lived in an apartment on the sixth floor of our building. I would walk up to the sixth floor every morning, stand outside her door and call out loudly, "Tsui Kit-ming! Tsui Kit-ming!" She would then come out and join me on our way to school. Sometimes, her mother would still be braiding her hair for her when I called, so I had to wait until she was done before we headed out. I can still recall her face. She had big black eyes, thick, lustrous and very black and frizzy hair. The frizziness was unusual for a Chinese. I was fascinated and kept wanting to touch her hair.

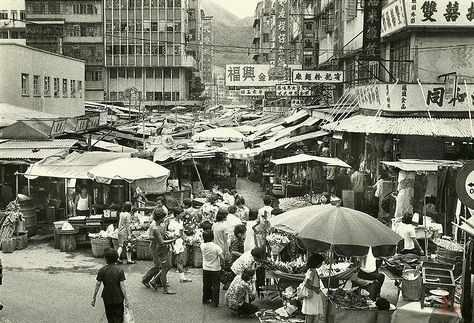

In those days, it was safe for kids to walk to school by themselves. It took us just over half- an-hour to walk to school together. We would talk incessantly as we walked, counting the rectangular patterns on the cement sidewalk as we went. Sometimes we would jump and skip a rectangle at a time, trying to see who could jump the farthest. Closer to school, we had to walk through almost ten busy blocks. Many of the stores had just opened, but they were already bustling with people. Street hawkers were everywhere, especially around the street corners, hollering at the top of their voices in their singsong tunes, advertising their wares. But the most aggressive ones were those selling cooked foods in their portable carts.

"Chu-ch'ang-fen....ah-ah-ah-ah......Yit-lak-lak-geh...chu-ch'ang-fen...ah-ah-ah!"

"Loh-bak-goh...ah-leh-leh-leh.....sun-hsin-yit-lak-geh....loh-bak-goh...ah-leh-leh…."

"goh jing jung.........goh jing jung.........."

The food carts were usually surrounded by people, grabbing a bite here and there before they rushed to work, or ran for their buses. There were rice rolls, dumplings, or  pan-fried daikon cakes with dried shrimps and barbecued pork. The choices were all tantalizing. In the midst of the heat, the steam and aroma coming from these food carts and the peddlers' songs, there was also the noise of passing trams, double-decker buses, honking cars, the ringing of bells by cyclists and the occasional yelling of a rickshaw driver. It was hard not to feel wide awake and our adrenalin flowing.

pan-fried daikon cakes with dried shrimps and barbecued pork. The choices were all tantalizing. In the midst of the heat, the steam and aroma coming from these food carts and the peddlers' songs, there was also the noise of passing trams, double-decker buses, honking cars, the ringing of bells by cyclists and the occasional yelling of a rickshaw driver. It was hard not to feel wide awake and our adrenalin flowing.

As quickly as the street hawkers set up their wares and foods, they could also disappear in less than a minute. Usually, someone would call out loud, "Zou-gueh! Zou-gueh! Cha-yan leh-la!" Those hawkers who only carried baskets and poles would move the fastest. Everyone would be scrambling to pack and run. Sometimes, a few customers would follow them into a back alley, or quieter street. They had to finish their business with the peddlers. Those with food carts would cover them immediately with sheets and push the carts away as fast as they could. Still, there would always be a couple of casualties. Before long, one or two policemen would appear on the scene, and those who could not run swiftly enough would have to surrender everything they had. Apparently, it was illegal to set up business anywhere, big or small, without a license. Street peddling was against the law. But Hong Kong in those days was filled with these wandering entrepreneurs. Without any special skills or capital, this was how many of them plied their trades and supported their families. It was a vibrant part of the local economy. Still, the police loved to chase after these little people. Grown-ups used to say that if a "sergeant" turned a blind eye to certain peddlers, it was generally believed that these people had been regularly "greasing his pocket."

As quickly as the street hawkers set up their wares and foods, they could also disappear in less than a minute. Usually, someone would call out loud, "Zou-gueh! Zou-gueh! Cha-yan leh-la!" Those hawkers who only carried baskets and poles would move the fastest. Everyone would be scrambling to pack and run. Sometimes, a few customers would follow them into a back alley, or quieter street. They had to finish their business with the peddlers. Those with food carts would cover them immediately with sheets and push the carts away as fast as they could. Still, there would always be a couple of casualties. Before long, one or two policemen would appear on the scene, and those who could not run swiftly enough would have to surrender everything they had. Apparently, it was illegal to set up business anywhere, big or small, without a license. Street peddling was against the law. But Hong Kong in those days was filled with these wandering entrepreneurs. Without any special skills or capital, this was how many of them plied their trades and supported their families. It was a vibrant part of the local economy. Still, the police loved to chase after these little people. Grown-ups used to say that if a "sergeant" turned a blind eye to certain peddlers, it was generally believed that these people had been regularly "greasing his pocket."

When I was about twelve, we moved into a slightly larger apartment in a building facing a busy street. Almost every day, Mom would send one of us to pick up something in a grocery store just below us, a couple of eggs that she needed for a dish she was preparing, or a piece of ginger or garlic that she forgot to buy in her earlier visit to the market. Mom used to say, "You siblings are the limbs of a body; Mom and Dad are the head and the trunk. We must all work together, sharing chores, helping out and looking out for one another as a family!" None of us minded running errands at all. In fact, it was something to look forward to as long as we knew we were close to completing our homework for the next day. With a whole team of willing foot-soldiers, and the shops just minutes away, Mom and Dad usually managed to run our home rather smoothly. But we had another reason to be so eager to help. For the ever-curious and fun-loving kid, there was really no shortage of drama or something interesting to engage her as soon as she stepped onto the street. Getting down to the street from where we lived on the fourth floor took no time at  all. We usually flew down whole flights of stairs, one by one. Gliding our hands along the banister and swinging the rest of our bodies forward, we would end up, after a big leap, on the landing. There were many shops on the ground floor of our building. Two grocery stores, an herbal shop, a tofu eatery which served fried bean-cakes and other soy products, and a bakery selling Chinese buns and western style desserts. There was also a shop that sold hand-carved mahjong blocks. We loved to hang

all. We usually flew down whole flights of stairs, one by one. Gliding our hands along the banister and swinging the rest of our bodies forward, we would end up, after a big leap, on the landing. There were many shops on the ground floor of our building. Two grocery stores, an herbal shop, a tofu eatery which served fried bean-cakes and other soy products, and a bakery selling Chinese buns and western style desserts. There was also a shop that sold hand-carved mahjong blocks. We loved to hang out in front of the mahjong store, watching the owner at work with his carvings. Now and then, an old man would come down the street with a stick and a circus monkey perched on his shoulder. As soon as the show began, facing a store, several passers-by would gather and kids would appear, as if from nowhere. After a few tricks, a lot of laughter and applause, someone from the shop would give the old man a few coins. He would give his thanks, move on to the next store, and bid his friend to do some new numbers. The crowd would follow him until they got tired of watching the same tricks, or when he finally moved on beyond the block.

out in front of the mahjong store, watching the owner at work with his carvings. Now and then, an old man would come down the street with a stick and a circus monkey perched on his shoulder. As soon as the show began, facing a store, several passers-by would gather and kids would appear, as if from nowhere. After a few tricks, a lot of laughter and applause, someone from the shop would give the old man a few coins. He would give his thanks, move on to the next store, and bid his friend to do some new numbers. The crowd would follow him until they got tired of watching the same tricks, or when he finally moved on beyond the block.

Once in a while, some travelling folk artists would also show up in our area. One of them usually carried a whole display of Chinese opera figurines made of colorful play-dough. The figurines were only about three inches tall, but very lifelike, and intricately made. Everyone could recognize instantly what they represented. You could tell from their expressions and what they were wearing famous villains, beauties and heroes, characters from classical myths, dramas and novels made popular in oral literature. The play-dough artist would sometimes do some singing and storytelling in front of the shops using his figurines as props. He was definitely one of my favorites. Whenever one of us got side-tracked like this during an errand and went home late, he or she would surely suffer a good scolding from Mom.

Once in a while, some travelling folk artists would also show up in our area. One of them usually carried a whole display of Chinese opera figurines made of colorful play-dough. The figurines were only about three inches tall, but very lifelike, and intricately made. Everyone could recognize instantly what they represented. You could tell from their expressions and what they were wearing famous villains, beauties and heroes, characters from classical myths, dramas and novels made popular in oral literature. The play-dough artist would sometimes do some singing and storytelling in front of the shops using his figurines as props. He was definitely one of my favorites. Whenever one of us got side-tracked like this during an errand and went home late, he or she would surely suffer a good scolding from Mom.

Not all the sights and sounds of Hong Kong are as interesting or fun to recall. Still, they often involve events or images rather unique to the place when I was growing  up. I can still remember lining up at a local clinic for several hours with my family one summer. A cholera epidemic had just broken out and many people had died. There was a sense of terror in the air. People had to line up for cholera vaccines. Mom and Dad repeatedly told us not to buy anything from food vendors, or to eat anything anyone gave us outside of home. Often, during the winter, we would experience water shortages and rationing because there was not enough rainfall the previous summer. We could only turn on our cold water tap for two hours every day. People scrambled to buy large metal or plastic containers to store daily water for their families. Every day, you could hear someone in the building screaming at those living downstairs to turn off their taps, so those living upstairs could get their water. Water is a precious resource. We've known that ever since childhood.

up. I can still remember lining up at a local clinic for several hours with my family one summer. A cholera epidemic had just broken out and many people had died. There was a sense of terror in the air. People had to line up for cholera vaccines. Mom and Dad repeatedly told us not to buy anything from food vendors, or to eat anything anyone gave us outside of home. Often, during the winter, we would experience water shortages and rationing because there was not enough rainfall the previous summer. We could only turn on our cold water tap for two hours every day. People scrambled to buy large metal or plastic containers to store daily water for their families. Every day, you could hear someone in the building screaming at those living downstairs to turn off their taps, so those living upstairs could get their water. Water is a precious resource. We've known that ever since childhood.

Hong Kong has come a long way. It came of age the same time that my brothers and I did. There was something special about this relationship. In this borrowed city, within a borrowed time, my family and many others had found a temporary shelter to nurture their young. Many did not plan to stay in Hong Kong for good. After all, who would want to live in a colony, being the ones colonized? It was also obvious that China would not be abandoning Communism any time soon. Eventually, our parents and many of their generation stopped dreaming of returning to China. Indeed, so many of us have moved on. A large part of my mature identity, as well as my brothers', was shaped in North America. Still, Hong Kong was the cradle of our youth and childhood. The sights, sounds and smells of Hong Kong as well as other rich memories of the place and her people have become an indelible part of our consciousness. Despite China's takeover, today's Hong Kong remains a multi faceted, hybrid city. And we are her hybrid children, children she has released to the world.