Jesuit Education, My Experience

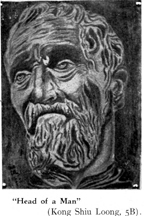

Kong Shiu Loon

Background

I entered Kowloon Wah Yan in November l951 to attend Class 5, and left it the summer of 1953, after completing Class 2. Fond memories abound from the experience of those three and a half years.

Earlier, I had fled from my home in Guanlan, about 50 miles north of Hong Kong. It was a time of unrest. Two days before the lunar New Year, I walked timidly to the Tien Tong Wei Railway Station and battled up the roof of a jam-packed train, bound for Kowloon. I was soon to be 15 years old.

Three months before, the Kuomintang government had vanished, after doing a massacre of anyone suspected to be a communist. The real communist, however, had gone to northern China not long ago, as part of the agreement for national unity reached in Chung Qing. They were the Dongguang Guerrilla Battalion (東江縱隊), well known in the area for fighting the Japs and rescuing foreign soldiers in Hong Kong. Bandits loomed. Almost every evening, someone would be taken for ransom. Being a member of a wealthy family, I was a sure target.

I was born in Hong Kong, the youngest son of my father who was a successful merchant; known for his philanthropic activities in the colony. An elitist in his generation, he believed that a good life was to build a large family, to uphold Confucian values, and to glorify one’s ancestors and motherland. With money made in Hong Kong he had bought land in his native place and built an elaborate village there for his family. The Japanese invasion of Hong Kong had shattered his dreams, along with those of so many others.

No one is prepared for the atrocities of war. People just do their best to survive. My father had three wives and seven sons, together with more than a dozen relatives and servants, each having his/her concerns. We decided to split to go separate ways to avoid being killed. Thus, three days after the Japs had taken control; I escaped with my mother’s cousin, who had been dispatched especially to fetch me to live with his mother, my mother’s aunt, in Zhenlong, a thoroughfare to Northern Guangdong. There I lived for eight months before meeting my mother in her home village to stay for a year, thence to unite with my father in the big family at Guanlan.

I had already experienced two days and nights of fear and robbery. Just before the Japanese landed, bombs were dropped, and extensive riots took place all over Hong Kong. Our home was visited by robbers nine times. Whoever carried knives or anything that could strike came to demand money and to take away whatever that caught their eyes. We were not alone. All streets were filled with shouts of “Sing Lee” (勝利) and other loud noises of rioting.

Uncle Lin and I started early in the morning. Neither mother nor I cried when we parted. To do something to survive was far more important than to grief. Uncle Lin carried me part of the way as we went north along Castle Peak Road. We passed two checkpoints and walked steadily through the hills and plain. Thongs of people filled the road. Soon, we began to see abandoned personal belongings. Then, there were injured people, crying orphans, and corpses. People passed them in silence. What I saw hastened my maturity, at nine, and later, helped me to learn to face the challenges of life realistically, grateful to the opportunities that time and people bring everyday.

We reached our destination two and half a days later to the warm welcome of my grandaunt.

Learning to Grow

In the ensuing years, I had lived a life as fully and richly that any growing boy could ask for. Schooling was sporadic. But life was a big school. We did not have newspapers, television or telephone carrying information. But there was no lack of stories of relatives and friends and neighbours whose lives were impinged by poverty, personal loss, fears and joy, conflicts and triumphs. People were engaged in making life better at a time when war and ideological conflicts interrupted, even negated their efforts. As a budding teen, I had learned all life skills, and experienced human struggles of success or failure that no school could teach.

School was about life too. Written on the walls of the assembly hall were four huge characters, li, yi, lian, chi (禮,義,廉,恥). At every morning assembly, we recited The Will of our National Father (總理遺囑), together with the 21 Rules of Youth (青年守則). No text book was available. We copied whatever teachers wrote on the blackboard and bound the pages together to make textbooks. But teacher-pupil relationship was very warm and genuine. Central in our learning was patriotism and self-actualization through knowledge, and devotion to family and community. Some of us got involved helping to fight the Japs. Later, on hearing the end of the war, all of us swarmed the camp to spit and slap the Japanese soldiers in defeat.

The war ended in August 1945. But there was no peace. China was immediately engulfed in two intensifying wars, one between communist forces and a corrupt government, and the other against a runaway inflation which made life impossible. My father died two weeks after victory day. My family too was engulfed in conflict struggles for individual interests. All male members left the village for Hong Kong except me. The decision was made, contrary to my wish that I should stay in the village to look after the family estate. No one foresaw the rapid turn of events after 1949.

Thus, in 1949, I returned to my birthplace bearing a complex past to face an open future. I entered Pui Sun English School to begin learning the alphabet at class 8. It was an excellent school where students were fully respected. The majority of the students were over-aged and new arrivals, like me. We learned each in our own ways, and we could advance to the next higher grade any time, just by request. The teachers were excellent too. They were devoted to teaching, and they had upright characters. I befriended to one teacher, Mr. Lai Kam, who was excellent in playing the violin. He was from a wealthy family in Guangzhou, and a graduate from the Sun Yet Sen University. He served as an interpreter for the American army in The China-Burma Road during the war. He initiated me to the appreciation of classical music playing Massenet’s Meditation from Thais, an exquisite sound that still reverberates in my soul today.

With the sudden and continuous influx of people from all over China, Hong Kong was not a calm place. Britain was a defeated country during World War II, poor and down in spirit. However, the surge of Communism in China and other countries made the colony an active place for international espionage. Churchill was quick to see the impending challenge of the communists, and warned about the effect of a Bamboo Curtain raised in this part of the world. Looming behind was the working of McCarthyism. In Hong Kong, the mechanism nicknamed Special Balloon was set up to keep people under watch.

Mr. Lai was openly jubilant with the news in the Sing Dao Daily, reporting the opening ceremony of the founding of the Peoples’ Republic of China. He was especially elated that the word liberation (解放) was used to describe the change in China. He left for Guangzhou ten days later to join the new liberating force. Another teacher who had inspired me to love classical literature went with him.

Mr. Lai had a long conversation with me before his departure. He left his prized processions with me, to be sent to him later “when I am more settled”, he said. It consisted of a set of ten hard-cover books of World Literature, a few records, and his violin. He told me that they were things that he had kept when he “went through bombs and showers of bullets”, and they had inspired his life all along. He also urged me to study hard and, when possible, to go abroad for higher studies so as to solidly serve our motherland. He said: “history will await your contributions”.

I received a letter from Mr. Lai three weeks later, telling me how wonderfully everything was working, and how he had finally embarked on the right path in serving our motherland. A set of five pictures came with the letter, depicting the official entrance of the Liberation Army to Guangzhou. Then it was silence. Months had passed before one day; a man timidly came to see me with a crumbled note from Mr. Lai’s sister. Thunder bolted. My teacher had been “taken away”, accused for being a Trotskyan. How final is that term “taken away”; how fatal the rhetoric.

Entrance to Excellence

Months passed. I had a strange dream one night in which I was addressing an international assembly, in English. I woke the next morning, determined to seek admission into a prestigious school. I walked to Nelson Street and asked to see the headmaster. Miraculously, Mr. Lim Hoy Lan received me. He asked me why I came when there was no indication of any recruitment. When satisfied with my answer he asked me to read three pages from Robinson Crusoe, and corrected my pronunciations with his heavy Singaporean accent. In the end, he told me, “you have come to the right place; we are happy to have you”, and led me to the third floor to introduce me to Mr. Ching Hing Chow, form master of Class 5. That began my lifelong association with Wah Yan. It opened up a world that I had not anticipated, even in my dreams.

Months passed. I had a strange dream one night in which I was addressing an international assembly, in English. I woke the next morning, determined to seek admission into a prestigious school. I walked to Nelson Street and asked to see the headmaster. Miraculously, Mr. Lim Hoy Lan received me. He asked me why I came when there was no indication of any recruitment. When satisfied with my answer he asked me to read three pages from Robinson Crusoe, and corrected my pronunciations with his heavy Singaporean accent. In the end, he told me, “you have come to the right place; we are happy to have you”, and led me to the third floor to introduce me to Mr. Ching Hing Chow, form master of Class 5. That began my lifelong association with Wah Yan. It opened up a world that I had not anticipated, even in my dreams.

Time passed, with unfolding events, hastening growth and change. There was no basic difference between Wah Yan and the schools I had attended before, like respect for the individual, devoted teachers, genuine friendship and freedom to learn. But it was for me a wider and more varied experience. It was also the first time in my life that I attended school with a relative stability.

Time passed, with unfolding events, hastening growth and change. There was no basic difference between Wah Yan and the schools I had attended before, like respect for the individual, devoted teachers, genuine friendship and freedom to learn. But it was for me a wider and more varied experience. It was also the first time in my life that I attended school with a relative stability.

However, tumultuous changes were happening in China to impact on that stability. Everything that could be taken from my home was taken away. The women of my family who stayed behind were ordered to parade in public, with their bodies tied together, and hands holding metal utensils to make loud noises to attract attention. On their necks were hung big placards with the words “Down with dirty landlords, exploiters of the people”. My elder mother died during one of those parades, and no one dared to bury her before her body rotted. Three nephews of school age were barred from school. They remained illiterate all their lives.

I had visited my mother in the winter of 1950 and the summer of 1952. She and eleven members of the family were living in segregation. The irony was that two of our former farmhands, who had been given land, came to me secretly to express their disappointment. They did not manage to have enough to eat. So, unlike the propaganda, fanshen (翻身) was not working for all people.

But the power of propaganda must not be underestimated. Among many of my friends and classmates in Hong Kong, study groups (學習組) were popular after school activities. They were cellular organizations, usually initiated by one or two high school students, to attract other students to meet and study. The purpose was to learn about the latest development in China, and to motivate one another to go there to study in the new universities. The grand purpose was to serve the new China, liberated and free. In the years before the big famine and the Anti-rightist Movement, a significant number of my generation followed the calling. Many of these students were sons and daughters from wealthy families and prestigious schools, intelligent and confident.

No one knew how these study groups came about. I got involved in one not long after I entered Wah Yan. I had already adjusted to my new school, enough to spend most afternoons playing basketball with classmates. One day, our team encountered a group from Diocesan Boys School in a match. We were invited to have a pop drink in a flat on Boundary Street after the game. It was a spacious flat, home of our host who lived there alone, served by a servant. He was the son of an overseas Chinese merchant in Thailand. There were eleven of us, eight boys and three girls. The latter were students of Maryknoll and St. Mary’s. We had plenty to eat and drink compliments of the host. He led the study with the opening remark “Our motherland needs us”, and we repeated it as a slogan. We then discussed the obligations of young people who would be masters of the future. There was information about studying in the many reorganized universities and technical institutes all free of charge. All we had to do was to make up our mind to join in, and report to the reception polls. In the end we were told to be secretive and keep on pondering until we had made up our minds to go together. Our study group met twice a week. Each time we finished the meeting by singing The Internationale (國際歌), a rousing song for any youth.

I attended the Group for three weeks until it was time for a decision. Four boys and two girls decided to go, causing heartbreaks to their parents. The rest of us remained, including Tim, our host. He later attended Cambridge, reading biology and chemistry. He became the founding chairman of a famous pharmaceutical firm in 1960. I decided to stay put largely on what I had seen and, from behind, the advice of my teacher who had paid heavily for his patriotism. Furthermore, I had earned my place in the sun after years of drifting. I would be ungrateful if I would not do my best to benefit from the serene environment of Wah Yan. The following are memories of my good days.

Sincerity

My first impression of Fr. John Moran was how frail he was, teaching us Hygiene. He had the face of a skeleton, with deeply sunken eyes and a pale complexion. It was before long that I discovered that he had not enough to wear. His hands shook in the cold winter days, and behold, through his hands holding the textbook, one of the sleeves had inside it a woollen sleeve, while the other was empty. One day, I asked why he would not wear enough clothes so he could be warm and healthy. He replied by telling us his personal story.

My first impression of Fr. John Moran was how frail he was, teaching us Hygiene. He had the face of a skeleton, with deeply sunken eyes and a pale complexion. It was before long that I discovered that he had not enough to wear. His hands shook in the cold winter days, and behold, through his hands holding the textbook, one of the sleeves had inside it a woollen sleeve, while the other was empty. One day, I asked why he would not wear enough clothes so he could be warm and healthy. He replied by telling us his personal story.

“I arrived at Guangzhou a young Jesuit priest…… It was dark after super. I strolled to the building adjacent to the church and saw a mount of unmarked boxes by one wall. I asked what they were, and I was told not to inquire……

“Later, I leaned about their contents and became very angry…..

“After extensive searching and prayers, I decided to lead a life of self-imposed hardship to continue serving my God….”

We were stunted hearing his revelations. In regretting that I had asked my question, I began to think how sincere he was, telling us his inner secret of so long ago. He was a shining example for all of us, not as a role model, but a man of dignity. In the Confucian tradition, a scholar serves his country in the court with his ideals and, when in disagreement with the establishment, retreats to the countryside and teach his ideals to the common people. In Fr. Moran’s case, his only ideal was God, and his will to serve Him was not to be bent by the authority of man.

Fr. Moran had inspired me to teach using personal stories. I have followed his example teaching teachers and leaders all over the world for more than fifty years. From the feedbacks of many students it is the most convincing way to tell any idea, or the truth.

Caring

The word caring has nowadays become a fad. Its real meaning is an unconditional concern for others, giving what one has. It is a word that characterizes Fr. Patrick Toner. He was my form master, English teacher, financial benefactor and Rector. Our encounters began with him teaching us chemistry in the small laboratory on the top floor of Nelson Street. He knew it was not a success, and he handed it to Mr. Chemistry, Wong Chin Wah, after a few weeks.

The word caring has nowadays become a fad. Its real meaning is an unconditional concern for others, giving what one has. It is a word that characterizes Fr. Patrick Toner. He was my form master, English teacher, financial benefactor and Rector. Our encounters began with him teaching us chemistry in the small laboratory on the top floor of Nelson Street. He knew it was not a success, and he handed it to Mr. Chemistry, Wong Chin Wah, after a few weeks.

Asour form master, he taught English. It was boring because he was teaching grammar all the time. However, we enjoyed watching him licking his chalk before writing, wondering why he needed calcium. But, lightening struck one day. He read an essay I wrote to class, and praised it as “having the mark of a professional writer”. It stirred everybody up, because I was not his favourite boy, and the praise was excessive. He then introduced us to great literature.

We went to Tai Po for our annual class picnic on a cold day. Seeing an empty football field, someone suggested a match. Fr. Toner was immediately enthusiastic and he participated. I was watching, and I saw a different person in him, totally lost in the game, like any teenager. He had his leather shoes on, and he was brave as a warrior. I had a bad omen. In a moment, he slipped on the damp grass ground and fell. He moaned and could not get up for a while. We had to carry him part of the way to the station. He became one of us.

It was on another sports event that his caring shone and impressed me to this date. We held the sports day at McPherson Grounds. The day had gone smoothly with only the last event to go. People were tired and ready to slip away. It was the Sixteen Hundred Meter Race, eighteen rounds in the field. Seven people competed. Two of them were trained runners. They finished first and second in a jiffy. Number three also soon reached the finishing line. For the remaining four, there were still ten rounds to go. The onlookers began to jeer, advising them to drop out, and shouting insults. Three runners bowed to public pressure after dragging two more rounds. But the last one, Ma Jr. persisted, continuing his run, ignoring the jeers.

Fr. Toner looked on very attentively. I saw Fr. Burke came to him to ask for the name of the boy. He told him the name, and added that he was the elder son of our teacher, Mr. Ma Yuk Lun. There were still six rounds to go and Ma Jr. persisted. Then, Fr. Toner ordered the secretary to run back to the school and find a prize item. He said to Fr. Burke: “This boy has an unusual character; he will finish whatever he started to do, regardless of what other people think or do. We must give him a prize for good sportsmanship.” The bell rang to signal the final round. The crowd became silent. Then everybody cheered when Ma Jr. crossed the finishing line. I looked at Fr. Toner. He wore a contended smile and walked blissfully to offer the “loser” a hearty congratulation.

Fr. Toner looked on very attentively. I saw Fr. Burke came to him to ask for the name of the boy. He told him the name, and added that he was the elder son of our teacher, Mr. Ma Yuk Lun. There were still six rounds to go and Ma Jr. persisted. Then, Fr. Toner ordered the secretary to run back to the school and find a prize item. He said to Fr. Burke: “This boy has an unusual character; he will finish whatever he started to do, regardless of what other people think or do. We must give him a prize for good sportsmanship.” The bell rang to signal the final round. The crowd became silent. Then everybody cheered when Ma Jr. crossed the finishing line. I looked at Fr. Toner. He wore a contended smile and walked blissfully to offer the “loser” a hearty congratulation.

I learned a big lesson of broadmindedness. I knew, and it was public knowledge, that Mr. Ma was a “sympathizer” to communist China, and his son had decided to study in new China once the school term ended. Under the spell of McCarthyism, the fact that Mr. Ma was teaching and being respected at Wah Yan testified the independent will of the Jesuits. And the respect and praise that Fr. Toner showed to Ma Jr. for running last in the race demonstrated the quality of his caring. He publicly awarded an act of simple human decency. The rest of us were taught a valuable lesson.

We moved to Waterloo Road when I was in Form 5, my final year at Wah Yan. Fr. Toner was our Rector. It was an eventful year for most students in the new campus, and more so for me. Despite the pressure of the public examination, we found time to pursue lots of non-school activities. My buddies and I got intrigued in cowherd recorders in early fall, enough not only to play, but also to make our own instruments to form a quartet. The knowledge that I had acquired treating bamboos while living in the village came in handy. We worked and practised hard, and soon we were rewarded with top prizes in the open music competition. Fr. Toner learned about our wins from the newspaper and got excited. I had never seen him so happy when he called us in his office to offer his congratulations. He enquired at length how we began and practised. He gave me a half scholarship that I badly needed.

In the spring, the Rector initiated an art competition. I entered with several drawings and paintings that I had recently learned to do. With a big surprise, I was given the honour of The Best Artist of the School. This time, Fr. Toner enquired about my family conditions and aspirations, and he encouraged me by exempting all my school fees.

In the spring, the Rector initiated an art competition. I entered with several drawings and paintings that I had recently learned to do. With a big surprise, I was given the honour of The Best Artist of the School. This time, Fr. Toner enquired about my family conditions and aspirations, and he encouraged me by exempting all my school fees.

Elitism

We had two ace math teachers, Mr. Pun Yau Pang and Fr. Burke. Mr. Pun had the habit of beginning every sentence with the phrase “now then now”. It probably meant “see, therefore”, an attention caller. He talked fast and not everybody could follow. But, he was aware of the progress of every student, and offered after-class tutorials to those who lagged behind. On the other hand, Fr. Burke was satisfied in interacting with the elite. In our case, he was Yip Tung Tsing. He was almost the only one who answered Fr. Burke’s questions in class. At one time, he got a mark of 101 for his paper in geometry, because he spotted an error in the question asked, and wrote down on it “This is impossible to prove”. Fr Burke drew our attention to it, and encouraged us to believe in ourselves when we felt right.

We had two ace math teachers, Mr. Pun Yau Pang and Fr. Burke. Mr. Pun had the habit of beginning every sentence with the phrase “now then now”. It probably meant “see, therefore”, an attention caller. He talked fast and not everybody could follow. But, he was aware of the progress of every student, and offered after-class tutorials to those who lagged behind. On the other hand, Fr. Burke was satisfied in interacting with the elite. In our case, he was Yip Tung Tsing. He was almost the only one who answered Fr. Burke’s questions in class. At one time, he got a mark of 101 for his paper in geometry, because he spotted an error in the question asked, and wrote down on it “This is impossible to prove”. Fr Burke drew our attention to it, and encouraged us to believe in ourselves when we felt right.

That took place in our graduating year. We were all confident. Since we had someone to answer the teacher’s questions, some of us felt free to enjoy other delightful activities in class. There was a good supply of tasty peanuts in the tuck-shop, ten cents a bag and we took turns to buy them to pass around during class. Many years later, I met Fr. Burke in Singapore to dine together. We were then teaching teachers. I told him about our naughtiness, and we had a good laugh. He admitted that he was not “the best math teacher people said I was”.

Congenial Friendship

Schools do not exist in a vacuum. They are an integral part of society. Students do not only learn to succeed in examinations. They learn to be good persons. A good school is therefore like Nature itself, all embracing, nourishing, and encouraging harmony and development. Our student population had a change from 1950 on, boosted by an influx of “Shanghai boys”. They came with their wealthy families fleeing China. The difference between us was big and sharp. Some of us originals had difficulty paying our monthly school fees. The newcomers showed their pocket money in thick piles of hundred dollar bills. They were also fluent in oral English and apparently bright. However, the advantage of youth made integration easy, especially in an environment of fairness. We soon became buddies, playing together, and caring for each other’s future.

We had plenty to explore in the outlying islands and beaches, swimming, catching crabs and making meals. The waters around had beautiful corrals then, and the rocks on the shores were works of art. We had an Olympic swimmer in our class who represented Hong Kong in 1952. He was Cheung Kin Man, nicknamed Tai Ping Shen Flying Fish. He swam like a real fish, unmatchable under water. Ten of us would form a circle at sea with him in the middle. At the call of a signal we would close in to catch him, and failed every time. It was lots of fun. He was a good basketball player too. He became a steward with Cathay Airline after graduation. I had the luck of enjoying the luxury of flying first class through the Pacific on his hospitality in the 1960’s.

We had plenty to explore in the outlying islands and beaches, swimming, catching crabs and making meals. The waters around had beautiful corrals then, and the rocks on the shores were works of art. We had an Olympic swimmer in our class who represented Hong Kong in 1952. He was Cheung Kin Man, nicknamed Tai Ping Shen Flying Fish. He swam like a real fish, unmatchable under water. Ten of us would form a circle at sea with him in the middle. At the call of a signal we would close in to catch him, and failed every time. It was lots of fun. He was a good basketball player too. He became a steward with Cathay Airline after graduation. I had the luck of enjoying the luxury of flying first class through the Pacific on his hospitality in the 1960’s.

Only a handful of us in the three graduating classes were sure to attend the University of Hong Kong. They had rich families to support them. The Shanghai boys were largely American bound. For those of us who wished to go on studying, there were the technical and teacher-training colleges, which were free. I had no plan at all. I had seen my father’s estate, which I was to manage, taken away overnight. I had seen executions, despair and injustice around me. I had lost a patriotic teacher who was dear to me. In my young mind, I believed that nothing worse than what had happened before would descend on me. But my classmates were concerned. They were pressed on finding something concrete for me.

A classmate approached me during recess one day. To this day I still cannot remember his name, with much regret. We did not hang out together. He was a quiet type, lean and tall, from Shanghai. He asked me if I was interested in applying for the Northcote Teacher-training College. I said I did not know anything about it. He explained what it was, and, sensing my indifferent attitude, offered to obtain an application form for me. “It is no trouble for me,” he said, “I live close to the college on Bonham Road, and all you have to do is to fill it out. I shall deliver it for you”. That fixed my career in teaching and later, social and international development. As I now look back into my fifty plus years of working life, I am convinced that a guardian angel must have worked through that classmate to guide me on. I have absolutely no idea what I would do if this kind classmate did not help me.

That was not the only example of classmate bonds. In 1997, right after Hong Kong had returned to Chinese sovereignty, I got a call from Charles Lee out of the blue. We had not communicated for 44 years. We greeted each other warmly at lunch. I told him I had been watching him on TV recently. He told me he had been following me in the news all the years. He told me he had been appointed a member of Legco two days ago and, looking through the budget for higher education, felt that proper adjustments should be made with professional advice. I gave him my views on the new administration, and declined his request for me to help. We saw each other at a public function about two years later, and he told me that I had been right.

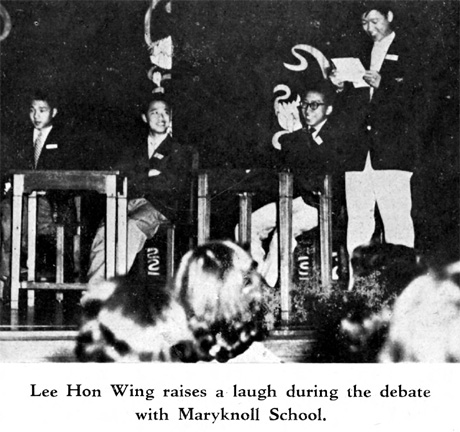

The example of Lee Hon Wing is different. We kept viable contacts as we pursued our separate careers around the world during half a century. I invited him to work with me as colleagues close prior to retirement. Then, he went to live in Australia. We continued to meet once or twice a year until he died. I know him well. He was perhaps Wah Yan’s poorest student financially. We had shared plain bread for breakfast many times. But we had pursued a rich intellectual and spiritual life. He had led a frugal life. In the end, he had saved a significant sum of money to set up a foundation to help educate poor children in China. He sailed to his final destination on the gentle breezes of Mozart’s Requiem.

The example of Lee Hon Wing is different. We kept viable contacts as we pursued our separate careers around the world during half a century. I invited him to work with me as colleagues close prior to retirement. Then, he went to live in Australia. We continued to meet once or twice a year until he died. I know him well. He was perhaps Wah Yan’s poorest student financially. We had shared plain bread for breakfast many times. But we had pursued a rich intellectual and spiritual life. He had led a frugal life. In the end, he had saved a significant sum of money to set up a foundation to help educate poor children in China. He sailed to his final destination on the gentle breezes of Mozart’s Requiem.

Sounds of Heaven

The pros and cons of segregated schools are still in debate around the world to date. Children growing up do need to associate with the opposite sex to lead natural lives, especially in their teen years. We were elated when Fr. Liam Egan led us to debate with the girls at the beautiful hall of Maryknoll Convent School, in our final year. The motion: “That, at the present time, girls should be excluded from doing higher studies in Hong Kong University” was successfully defended by the girls. They won the debate. We were happy that we lost, fancying that our participation in the event would help to forge a closer relationship between our schools.

The pros and cons of segregated schools are still in debate around the world to date. Children growing up do need to associate with the opposite sex to lead natural lives, especially in their teen years. We were elated when Fr. Liam Egan led us to debate with the girls at the beautiful hall of Maryknoll Convent School, in our final year. The motion: “That, at the present time, girls should be excluded from doing higher studies in Hong Kong University” was successfully defended by the girls. They won the debate. We were happy that we lost, fancying that our participation in the event would help to forge a closer relationship between our schools.

Maryknoll Convent School had the finest architecture and the most beautiful gardens, especially in spring. But the luxurious hall and the artistic lightings stunted us the minute we got inside. The graceful girls and their ease in speaking English also humbled us. We were served tea and home-made niceties after the debate. But the zenith of my experience came when the nuns accepted Fr. Egan’s request to sing. Nuns were not allowed to sing in public. So they performed from the balcony. Heavenly sounds descended as they delivered Schubert’s Ave Maria. Then, they sang Miserere mei, Deus. I was totally moved. As the choir pleaded “create in me a clean heart, O God” and the treble rose up and up as if of no limit. I shook from my heart. I learned for the first time that music could be sublime.

Fr. Egan and I became colleques and neighbours teaching at Nanyang University in 1960. We had a few quiet late afternoons together. By then, I had my baptism in the antiquities and Western culture, having completed my Ph.D. degree from a Catholic university. I thanked him for that experience at Maryknoll long ago, and we shared our appreciation of that seventeen century Renaissance polyphony by Allegri. He was a very learned man.

The Praying Tree

My memory fails me as I try to recall how Fr. Morahan turned out to teach us poetry in our final year. There was enough to do preparing for the public examination. But he managed to squeeze in a tight curriculum something new. He emerged from no where and his role was not clear, certainly not our English teacher. He was a big man. But his voice softened as he enjoyed reading the rhythm of his favourite poems, often keeping his eyes closed.

My memory fails me as I try to recall how Fr. Morahan turned out to teach us poetry in our final year. There was enough to do preparing for the public examination. But he managed to squeeze in a tight curriculum something new. He emerged from no where and his role was not clear, certainly not our English teacher. He was a big man. But his voice softened as he enjoyed reading the rhythm of his favourite poems, often keeping his eyes closed.

He began with Under the Greenwood Tree by Shakespeare, a motivator. Then he went for Robert Frost with The Aim Was Song and Wild Grapes. I liked the latter, and I still remember the final lines:

The mind is not the heart

I may yet live as I know others live

To wish in vain to let go with the mind

Of cares at night to sleep but nothing tells me

That I need learn to let go with the heart

One day, Fr. Morahan came to class in a showy mood. He recited by heart Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village, all 430 lines. We enjoyed the rhythmic flow of his soft voice. But we did not get much of the poet’s lament for the loss of pastoral beauty as man advanced to modernity. Then, he spent two periods teaching us a 12- line poem by the American poet Joyce Kilmer, Trees. He made sure that everyone could recite it and appreciate its beauty:

I think that I shall never see

A poem as lovely as a tree

A tree that looks at God all day

And lifts her leafy arms to pray

Poems are made by fools like me

But only God can make a tree

Fr. Morahan might or might not know the power of the little tree that he had planted in me. It gave me the courage to approach the University of Ottawa the same way I approached Wah Yan, having little to show, but a burning desire to learn. One early morning in October, 1958, I arrived at the office of Fr. Shevenell, Dean of the School of Psychology and Education of the University of Ottawa. He asked me what I would like to do and, after hearing my wishes, assigned 12 courses for me in the first term, more than a double load for other students. Ottawa University was then still a private institution, maintaining compulsory theological studies. My classmates were largely priests and nuns, some of whom were scholars in their own rights, like Fr. Gordon of Loyola, Fr. Rene of Georgetown, and Mother Beatrice of Philadelphia. Quite a few were Jesuits.

I learned happily in that rigorous environment, taught by Renaissance professors and helpful peers. I completed two graduate degrees in two years, well in advance of the requisite time. Fr. Morahan died in l992, in Mayo, Ireland. He would be pleased with the outcomes of the extra efforts he made four decades ago.

Poetry is the medium of communication with the mind and the heart speaking in unison. I attended the World Congress of Jesuit Alumni/ae in 1979 with the theme “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high”, a line by Tagore, the eminent poet of India, a Jesuit alumnus. The speeches and discussions were heavily laced with famous poems. In the end, a resolution was reached which became the motto of present day Jesuit education. It was from Gurudev’s poem, saying: Your shared past has a common future, your history is prophecy, the privilege of your education directs you to meet the challenge of reaching out to others in need.

Continuity

Put differently, “history is prophecy” means continuity. It is an important concept of life when we strive to better ourselves, from past to present onto the future, creating meaning in a temporal existence. I kept contacts with Mr. Ma Yuk Lun after leaving Wah Yan, maintaining a consistent correspondence in the three decades when I was away from Hong Kong. He was ready to give counsel whenever I asked for it. He told me, when I was Chair Professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong, that I might be more learned, he was still my teacher. He also wrote to tell me that, when he was undergoing treatment for NPC at the Queen Mary Hospital, attending doctors who were past students carried him on their backs to show their affections. In the end, when he was about to go, I told him I would come to see him as soon as I could get away from Toronto. He wrote back to stop me, quoting the lines: “Be not concerned of being together in person, be concerned that our hearts are not in synergy”. (不患不相見,只患不同心).

Mr. Ma had his ways in maintaining continuity. He introduced me to Mr. Anthony Ho when the latter was preparing to emigrate to Canada.

“You can help each other,” he said, “He is a good man”.

Immigration is a trying process when one uproots everything that was established in one place to go to a new land where the future is full of uncertainties. Only those who are brave and tenacious can succeed. Mr. Ho had a survival plan in how to feed his growing family at the time. But I advised him against it. He had impressed me as a perfect teacher when we first met. His face beamed with the shine of kindness, together with utters of joy, whenever our conversation touched students and schools. It would be a loss to the public if he would not continue to do what he did best.

I helped him to establish the York Herbart School in Toronto, to help many students to access their university education. Then, after retirement, he continued his service by helping Wahyanites to establish the wykontario blog so they can enrich each other’s lives. Thus, the Jesuit philosophy of homines pro aliis (men and women for others) continues in the electronic milieu, transcending time and space.

A Renewing Tradition

The core of continuity is tradition, in which personal identity and dignity dwell. As I write, I am grieved that the new administration of HKSAR is dong its best to abolish the fine tradition of school diversity established in centuries. Schools must now follow the narrow directions of uninformed beurocrates. Each school is an entity, with little regard to society and tradition. Under the rhetoric of school-based administration, education matters are being decided by a school council made up of voters, teachers, parents and students. Democracy, in its twisted sense, is now god. Those in positions of power are forgetting that children must, and need to learn from experienced parents and teachers who know better. They should know that schools are not political playpens. And, when children are deprived of the opportunity to learn to respect tradition and authority, they will grow up rootless, unable to maintain a clear identity which is so important at a time of rapid change.

What are the marks of a good education? Voltaire, whose ideas inspired the French Revolution, wrote on his own education in 1746, when he had already rebelled against the Church. He said,” What did I observe during the seven years I spent under the Jesuit roof? A life of moderation, diligence and order. They devoted every hour of the day to our education or the fulfilment of their vows. As like myself, many others were educated by them”. Could a revolutionary, who espoused freedom and democracy, value the inculcation of moderation, diligence and order? History proved so. Descartes, Moliere, James Joyce, and in our day, Kennedy and Trudeau were distinctive Jesuit alumni.

The life and thoughts of St. Ignatius was shaped by these same values, as he went through battles, imprisonments, meditations, prayers, studies and pains. He had many visions, beginning with the one when he saw Creation “in a new light that we can find God in everything”. Therefore, man is free to act, instead of following what is fixed. He also understood human nature when he wrote in his Spiritual Exercise, that “not only the intellect but also the emotions and feelings can help us to know the action of the spirit in our lives”. His perception of the functioning of the whole human being preceded the current psychological panacea of EQ by 400 years.

He returned to school to learn basic Latin, literature, philosophy and theology when he was 33 years old, with humility and dedication. At the University of Paris, he worked out the Motto for his mission: Ad majoriem Dei gloriam (For the greater glory of God) and, after much deliberation, added inque hominum salutem (and the salvation of humanity).

The meaning of humanity in the Renaissance tradition comprises human dignity and services to others. It grows out of Love. It is now universally recognized that the United States of America has the soundest education establishment, because diversity is guaranteed by the Constitution. A very important mark of that diversity is the role played by Jesuit schools and universities, numbering thousands. The core of studies is the humanities. It became Liberal Education, and now General Education, with history and traditional wisdom as foundation. Thus, the milestones of educational wisdom are marks of tradition. Human beings will be reduced to robots existing in mere coping if traditions were allowed to fade together with excellence.

I am grateful to my teachers and the Jesuit tradition that I have learned to appreciate life in its brilliant richness. They have taught me man’s sublime dignity and his obligation to serve. I would not have known and practised them if I was not lucky enough to spend the short time that I did in my Alma Mater.