China Meets the World (2) - Psychology Links

by Kong Shiu Loon 江紹倫

Not a Simple Task

My mind races across time and space filled with all kinds of images and questions, as I stand in front of this special audience of psychologists trained in the Soviet Union of Russia. The time is June 23, 1981, just after the official announcement that China would spearhead into the Four Modernization process. My task is to speak on the recent development of Psychology in the West.

A more exciting announcement of the day is that intellectuals are now a part of the workers class. They are therefore an important force in the economic construction ahead. For almost two decades before, intellectuals were deemed a renegade element of society, to be purged and struggled against. Many were sent to live and work in the countryside, and to learn from the poor peasants.

The place is Shanghai. Professor J. N. Hu of East China Normal University, a PhD graduate of Chicago University, class of 1931, has made this special arrangement for me to speak, after very careful deliberations. We met nine years ago when I led the first group of overseas professors to visit China. He had asked me then, if I would help to vindicate (平反) psychology when the opportunity allowed. Psychology had been branded imperialistic and a “white flag” at the outbreak of the Korean War. It was totally banned in China.

The official host for the occasion is the Biology Section of the Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai Branch. Psychology of the Pavlovian brand had existed in biology studies and research. So, before psychology per se could be revived in China, this is the platform to prepare for it. Professor Hu could not be present to chair the session because he is not a member of the academy. He had introduced me to someone else who will do the job.

In the brief moment when my host was introducing me as a Professor of the University of Toronto and my research and writings, I have the time to decide what to say and how to cover such a vast subject in two hours. My heart leaps in bounds, as I remember the tumultuous events since 1964, and the hundreds of people that I directly and indirectly know who suffered from severe punishments, just because they had knowledge. I realize the gravity of my task. The fact that I am standing before this group under the auspices of the Academy represents a turning point, not only for Psychology, but also for the place of knowledge in current Chinese history.

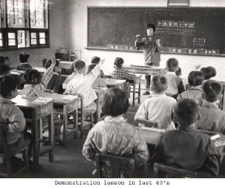

What was totally absurd had occurred in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (無產階級文化大革命), a movement when children and youth were officially encouraged to stop going to school and to turn against their elders and history. And, more recently, there immerged in national propaganda, the Blank-paper Hero (白卷英雄), as the role model for students of all levels. It was an outright denial of learning and knowledge. Fortunately, common sense returned. The universities were reopened again in 1977. Deng Hsia Ping visited Singapore and Japan in 1978. China was set in the long process of building A Special Socialistic State, Chinese Style (中國式的社會主義). There is now a realization that Psychology has played an important part in the world outside of China. It should be revived to help China meet the world.

What was totally absurd had occurred in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (無產階級文化大革命), a movement when children and youth were officially encouraged to stop going to school and to turn against their elders and history. And, more recently, there immerged in national propaganda, the Blank-paper Hero (白卷英雄), as the role model for students of all levels. It was an outright denial of learning and knowledge. Fortunately, common sense returned. The universities were reopened again in 1977. Deng Hsia Ping visited Singapore and Japan in 1978. China was set in the long process of building A Special Socialistic State, Chinese Style (中國式的社會主義). There is now a realization that Psychology has played an important part in the world outside of China. It should be revived to help China meet the world.

In an instance, I have decided to deal with the key issues, revolving the mind and the heart, materialism and idealism, subjectivity and objectivity, truths and untruths, individual rights and collectivism. If China was to meet the world, her decision makers must put away the entrenched dualistic mind, and approach the world as it is, a multi-dimensional constellation.

Not an Ordinary Journey

I make a quick survey of my immediate environment. I have no idea who are among the forty some people gathered in the room. I assume most of them are holding key positions. It is a very hot day. The air is still and muggy. The room has no ventilation other than a door and an open window. Everyone is wiping off sweat and waving a fan or something to stir up what could only be hot wind. It is two o’clock in the afternoon. Perhaps the only thing I can do is to ease people’s minds and to get near their hearts. I begin by telling the story of myself.

I went to Canada in 1958 to study at the School of Psychology and Education of the University of Ottawa. I had 500 US dollars with me, all the money I had. The school fee was 400 Canadian dollars. Because the Canadian dollar was higher than the US dollar, I had about 30 dollars left after paying the school fee and a $15 rent for my room not far from the School. I ate plain bread with tap water for meals during the first three weeks, before I got a part-time job.

I went to Canada in 1958 to study at the School of Psychology and Education of the University of Ottawa. I had 500 US dollars with me, all the money I had. The school fee was 400 Canadian dollars. Because the Canadian dollar was higher than the US dollar, I had about 30 dollars left after paying the school fee and a $15 rent for my room not far from the School. I ate plain bread with tap water for meals during the first three weeks, before I got a part-time job.

My room was a cosy little thing, a 90 square feet space on the attic of a Victorian style house. It was a narrow room, stretching 17 feet from door to window, and 6 feet in width on the first 11 feet from the door. That was enough space for a narrow bed and a small desk standing in parallel. I had to hop over my chair to go to the window to peep outside. The slanting roof tapered down to touch the inside of my bed so I could only sit upright on the outside edge. There was a small electric hotplate for me to cook my meals. It was placed on top of a wooden orange box next to one end of the desk. The empty inside of the box became a good shelf for my books.

My part-time job as a waiter at the Cathay Restaurant in China Town was a God-sent. About half of the customers in the evenings were government officers, Members of Parliament, and diplomats from various countries. I learned a lot about Canada and the world from their conversations. My pay was 50 cents per hour. But there were gratuities. So, working for weekends during the school year, and winter and summer holidays, I managed well financially.

Students took 3 to 6 courses per year on average. I took 12 courses and a part-time job. It meant that I did not have much time to sleep. However, for the two years that I was in Ottawa, it was the happiest and most intellectually rewarding time in my life. I was 26 years old when I completed my Doctor of Philosophy Degree in the most complex academic disciplines of Psychology and Education.

I began that journey a naïve young man. On my way to Canada from Hong Kong I carried three books, a Universal French Dictionary, an English Chinese Dictionary, and a Pavlov Complete Works in Chinese. I had the last book for no other reason than that I saw it in the bookstore, 679 pages for $1.30. It was cheap, formidable looking, and I believed I could read it easier than an English book in the same subject. I did not know that it was not useful. I was overwhelmed by so many books and journals that explained the wonders of man, of which what Pavlov had to say was a minute part.

“That book was useful in a different way.” I say, trying to end the first part of my story with a lighter touch, “I used it as my pillow because my bed sacked as soon as I lay down, and I needed a hard object to rest my head.”

There is no stir; not even a grin among the blank faces. But nobody is dosing in the suffocating heat. I am encouraged that I have won their attention.

Many Cross-roads

I continue my story with a non-contentious quote: “wonders are many, but none is more wonderful than man”. It is what Sophocles had written on the entrance wall of the Apollo Temple in Delphi long ago.

“Is man a wonder?”

“Do wonders exist?”

I asked, knowing that my audience would not give any answer. But questions like that do challenge people to think privately. They are like geminated seeds that would grow into sprouting plants.

I told the group that my classmates were largely very religious people, predominantly Catholic priest and nuns. There were a few Americans who had fought in the Korean War, a Hungarian refugee, several French Canadians, and me, a total of 47 people. I was the youngest.

My first class in the course Epistemology was taught by Professor Antonius Paplauskas Ramunus, a Russian refugee who was a Renaissance scholar, having a good command of seven languages and an extensive knowledge in many disciplines. He was deeply religious too. The first big question that he had to help his students settle was to distinguish between theological knowledge and other forms of knowledge, such as philosophy, science, and common sense. Without a clear concept how these different levels of knowledge were derived from, we would muddle in endless arguments of what man is, a being created by God, or a being in evolution, a part of a yet unknown process in Nature.

“How do we know?” he asked. “And how do we know what we know is true?” he asked further. Those questions were enough for our class to discuss for three hours, the entire duration of that first meeting. There was no convincing conclusion. I did not participate in the debate. But I realized, for the first time, the complexity of learning and knowing, and how involving our mind and heart and brain could be in the simple act simply called “knowing”

Professor Ramunus began the second class by writing on the blackboard “operation defines being”. He then proceeded to explain that knowledge was defined by the actions we take in order to know. His explanations took the rest of the year to complete, citing the wisdoms of sages from all ancient civilizations, including Egypt, Greece, India, China and others. It became clear that the operation of theological knowledge was to believe, which, in the case of Christianity, was born from grace, a gift of God. The operation of philosophy was reason and logic, and there were many kinds of philosophies, depending on the knowledge sought. Science was uncertain knowledge based on probability. Common sense was a product of experience. That course set our thinking free as we explored the diverse issues of the nature of man, and how he strives to be free and creative since the beginning of time.

With that bit of personal story set aside, I return to my questions to give some answers. Human beings are wonders because each one of us is different. That difference can be seen from the standpoint of materialism. But, each person also has unseen aspects and potentials, which can be actualized or ignored or suppressed. These are also real and existing, although they do not exist in material forms. The unseen aspects of individual persons are numerous too, as each of us knows privately. Thus, it would be presumptuous for any psychologist to explain or control human behaviour from a single perspective, like Pavlov’s conditioning. Indeed, it is wrong to do so.

Everybody’s life is characterized by growth. Growing freely can lead to creative and diverse achievements. But, growing in a restricted direction, or in response to a fixed ideology, would lead to a single outcome, namely, individuals subservient to commands. A person’s life is like the life of an academic discipline, proceeding along paths with many crossroads, needing choice decisions. It seems China is now standing before a crossroad, to adopt an open approach to study Psychology, or to remain in a confined understanding of it.

The Mind and the Heart

I saw a solemn mood showing in the faces of most participants in the room. It is time to drive the core of my subject matter hard into their minds and hearts.

I presented an outline of the overall development of modern psychology in the world in the past century, and the expanding application of the knowledge gained during that time.

In retrospect, it was America’s sudden entry into the Second World War that made the application of psychology an influential social force. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour woke up the United States to forgo its bystander position in the conflicts and killings in the world. Overnight, tens of thousands of young people were drafted into the army to fight in the Pacific and Europe. They came from diverse socio-economic, educational and racial backgrounds. They had to be trained in a large number of effective programs for war tasks. They also had to be dispatched appropriately to different groups and responsibilities. That was the most testing task of human management in history, especially when everything must be done in fairness, in emergencies, and in the critical life-death moments in the battleground.

The core issue is to identify the many ways in which human beings are different, to respect those differences, and to utilize them in most efficient ways to achieve a common good. So, all existing knowledge in psychology and sociology were applied. In addition, new knowledge and technologies for understanding human behaviour must be gained quickly, through vigorous research and development efforts. Later, after the war, the same efforts were made to serve the worldwide expansion of American trade and politics.

Thus, modern psychology and the social sciences developed not in a vacuum, nor in confined laboratories. Instead, it grew with human development in the context of history, responding to social and international changes. It is not a question of it being imperialistic or otherwise.

Basic to the core issue is the respect for the individual and human nature. The world had seen how Hitler used the German ideology of Marks in his attempt to conquer the world. He failed because he disregarded the rights and idiosyncrasies of individuals and believed in a collective power under his ruthless command.

Collectives did work well in emergencies, such as seen in the success of the Kibbutz of Israel in the early days of nation building. But they are doomed to fail at times of peace and stability, because individuals are then back to themselves, acting according to their basic nature as masters of their own lives. It is not difficult to arouse young people to join the collective by singing the Internationale, or similar songs. That is the heart working. But, in moments of quiet contemplation, people’ minds would tell them that the very name of a collective means the minimization of individual ingenuity and, without individuals actualizing their unique abilities and potentials, the collective is only a working machine.

Psychology is the study of the whole person, as individuals and members of families, groups and communities. Psychology itself is studied from many vantage points too. In the two years at Ottawa, I had taken 21 graduate courses in that field, courses like Individual Differences, Personality, Counselling, Dynamics, Learning. Cognition, Emotions, Testing, Psychophysics, Linguistics, Methodology, Statistics, Behaviour modification, History of Science etc. The School offers more, a total of 48 different courses. So, psychology is an open field, attempting to explore and understand the wonders of man, an open, self-striving and creative being.

Pavlov in Perspective

I turned back to Pavlov, perhaps the part about him that my audience did not know. I asked: “Do you know the life of Ivan Pavlov?” knowing also that nobody would answer.

Pavlov was born in a very religious family, with his father and maternal grandfather being ministers of the church. He was to follow their footsteps too. But Alexander II initiated free public education just in time. He entered a public school instead and, in time, studied science at St. Petersburg University. It was the time that Darwin and Sechenow had exerted important influences in the study of psychology. Pavlov followed the latter’s Reflexes of the Brain to study experimental medicine, focusing on the digestive process. By chance, he noticed how dogs which were fed with a ringing bell would, in time, secret stomach fluids and saliva when they heard the bell. This eventually led to the discovery of “conditioning”, a psychological process that influences our understanding of many aspects of behaviour, like learning, habit formation, memory, behaviour modification etc.

However, Pavlov denied that conditioning was a psychological process. He also refused to be identified as a psychologist, even in the final moment of his life, preferring to be called a physiologist specializing in brain reflexes. At some point in his research, Pavlov did suspect that it was the dog’s mind that drove it to secret digestive fluids on hearing the bell ringing. But he did not believe that consciousness existed, he called what he observed a physiological phenomenon. He even threatened to shoot colleagues in his lab if anyone ever uttered the word psychology.

In the United States of America, the study of psychology was dominated by “behaviourism” when Pavlov was doing his research. Edward Thorndike and John Watson were doing similar experiments. The latter even insisted that only those behaviours which could be seen would constitute the object for psychological research, a totally materialistic approach. These psychologists discovered a number of principles, including “association” and “exercise”, and they explained how learning could be enhanced by external forces, such as manipulating the stimulus to trigger predicted responses. The famous S---R connection of behaviour was thus born.

However, America was an open environment where psychologists were not adamant on limiting their research to singular beliefs. Instead, the easy flow of ideas and conjectures helped them to recognise the wonders of human beings. Thus, in the space of over a century, ideas and research attempts thrived, including brave probes into the hidden dimensions of the mind, the heart, as well as the brain.

In perspective, the concept of conditioning has led to the development of many useful technologies, such as behaviour modification and human engineering. B. F. Skinner has successfully taught pigeons to play ping pong. Brain-washing has been used for propaganda, advertising, industrial training, and the treatment of prisoners of war, and so on. But, if psychology is to serve human beings as free and creative agents, it should enhance their wellbeing rather than control them. That is the direction that Humanistic Psychology takes.

Self and Others

Humanistic Psychology explores human beings as individuals, and as he relates to others in harmony and conflict. A person who knows himself will know the purpose of life, and strive to achieve happiness and fulfillment. A person who does not know himself will just respond and cope, merely following external orders. The former is free while the latter is not. The former has dignity while the latter has mere existence.

The philosopher Hazel Barnes explains dignity like this: “Man’s dignity stems not from his having been given a favoured place in the universe but from the fact that while his existence is contingent, his life is his own creation.”

Buddha says it in another way:

Be ye lamps unto yourselves

Be your own reliance

Hold to the truth within yourselves

As to the only lamp

Our own Chinese culture recognises dignity in many ways since long ago. For example, Laoze said it like a psychologist when he wrote:

He who knows others is wise. (知人者智)

He who knows himself is enlightened. (自知者明)

He who conquers others is strong. (勝人者力)

He who conquers himself is mighty. (自勝者强)

Today, Laoze’s saying is often used in leadership training programs throughout the world. Modern psychology has discovered that human beings have two basic needs. One is to be sure of a personal worth confirmed by others. The other is to respect the value of other people. It is in the satisfaction of these needs that we have the team-spirit at work, a basic force in human resources development in all organizations, including family, school, and the work place.

From 1960 on, gallant attempts were made to improve teaching at all levels, focusing on freeing the student to learn. Antonius Paplauskas Ramunus, an influential philosopher after World War II, describes this focus clearly when he said: “The right of the child to be educated requires that the educator shall have moral authority over him, and this authority is nothing else than the duty of the adult to the freedom of the youth”. My own book Humanistic Psychology and Personalized Teaching, published in 1970, also describes this trend which is still viable today.

Subjectivity and Objectivity

Ideas and feelings expressed by a person in words or narration is a subjective opinion. Sometimes it might be called a subjective truth. On the other hand, a systematic collection of such opinions becomes an objective statement, sometimes called truth. However they are called, they all grow out of basic human needs. Psychology studies all aspects of these needs, as well as how they impact on individuals and society.

“How can this be done scientifically?” I ask, also sure that no answer will come from my audience. But, for people who grew up in an environment in which asking questions is a dangerous act, questions would linger in their minds to produce answers in time.

I continue to answer my own question by quoting a famous scientist, thus showing objectivity. Albert Einstein once said, “The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking”. So, science is a kind of common sense, only more disciplined and refined. It does not even have to be materialistic. Einstein says thinking. Is thinking a matter? No. Is thinking true and real? Yes, even when we cannot see or touch it. People express their thinking in words and other nonverbal forms. Love and affection, for example, are often expressed in special eye-contacts or hugs. Hate, on the other hand, could be expressed by killing. These are also subjects of psychological research.

We have only one single Chinese word (心) to represent mind and heart. This same character also means love and affection and caring, as in “have a heart” (有心) or (関心). The word heart, in English or Chinese also means the organ in our body which pumps blood to keep us alive, a matter. Then, as we say “you have no heart”, it does not mean that the person is without a biological heart. It simply means that he has no caring feelings. We now use two Chinese words to denote the English word mind, as in (心智). But then, it gets us into trouble, because the second word means intelligence and wisdom. All these show that psychological descriptions and research have a lot of difficult problems. But it also shows that it is very interesting and challenging.

By the time I went to Ottawa to study psychology, people were ready to go further and deeper. On the one hand, scholars all over the world were questioning human nature because of the atrocities of war. We realized that animals kill only for food and survival. And they also do it sparingly, wasting nothing. But human beings kill one another over an ideology, just a believed thought. And they do it en mass, in the cruelest ways. Does it mean that the human mind could be perverted at times, and the heart evil?

At the same time, American consumerism has pawned the human condition in exchange for greed, conflict, and unrest. Psychological wars in their varying forms became rampant. And peace was in compromise, both in spirit and in physical environs. For the individual, physical and mental heath has become a major concern. In response to it hylomophic medicine emerged to help.

In time, services derived from Social Psychology, Counselling and Psychiatry have become basic needs, expanding as society became more complex and controlled by the military and international corporations. The human condition became contorted as people were subjected to all kinds of psychological pressure; resulting from displacement in space, consumerism, and information overload.

Fascination in technology has pushed psychologists to study language, symbols, simulations, communication and virtual representations. By the middle of the 20th Century, the process of knowing got on a new platform, where knowledge was expanding in both size and speed, demanding the learner to learn in ever faster speed. One of my classmates got interested in the exploration of artificial intelligence. The task was to describe intelligence so precisely that it could be tested and simulated by a machine. I remember how we all questioned him when he presented his research plan. He was raising questions on the nature of the human mind and the limits of scientific hubris. But he succeeded eventually, after six years of hard work.

The mind machine is not new. Ancient Greek myths, like Talos of Crete and Pygmalion’s Galatea, had predicted long ago how the mind could be systematically deciphered. Automations appeared in ancient Chinese and Indian myths as well. But it is the combined use of cognitive psychology, mathematical logic and engineering that built Programmed Learning and Teaching Machines. They were soon used in the schools in the two decades after 1960, just before the emergence of the desktop computer, a convenient tool for information procurement and interaction.

However, it is the heart that decides when and how machines would be used. The heart also drives the mind to work or go lazy. It dominates most human affairs and defines character, especially seen in our own Chinese culture. Both Confucius and Mencius went to great lengths describing the concepts of ren and yi (仁義), in which dwell human compassion, sympathy, empathy, caring, and gallantry. It is the emotion in its various forms which drives behaviour, and shape the quality of life.

Science and Aesthesia

The functions of science are prediction and control, using probabilistic methods. Psychology uses the same methods for the same functions. In addition, it attempts to describe phenomena perceived in fact as well as in imagination. We can now test a student and calculate the probability of his academic success, using his intelligence and aptitude scores. The margin of error is about 30%. If a student is given effective guidance and psychological counselling, such predictive errors could be reduced to about half, good enough for parents concerned with how their children do in school.

Comparatively, the prediction of success in the launching of a rocket into space must be very precise, with error margins one in trillions. This can be done because all the parts and their interactions in a rocket are objectively fixed. On the other hand, human behaviours are open and varying. We cannot even identify all the variables affecting a person’s behaviour across space and time, and in social interactions. So, psychological predictions are often relative rather than absolute.

Recent insights from the behavioural sciences have expanded our conception of man as an active, seeking, autonomous and reflective being. He learns, driven by aesthesia and aspiration from inner forces, rather than in reaction to outside stimulus. He assumes responsibility for his own wellbeing when he feels free and secure. It is this conception of man that is now the subject of psychological exploration.

To conclude my lecture I turned back to my own experience. I told my audience how I chose to study Psychology 26 years ago. I was teaching in a government school in Hong Kong. My job was commonly regarded as a Golden Bowl, with a salary that would enable me to purchase a small flat for investment every year, and fringe benefits which kept me free from any worry. But I wanted to be myself. I read Tolstoy’s narration of man and decided to resign from my job, and went to study Psychology and Education. Tolstoy said:

“One of the most widespread superstitions is that man has his

own special, definite qualities….Men are not like that….Men

are like rivers….Every man carries in himself the germs of

every human quality, and sometimes one manifests itself,

sometimes another, and the man often becomes unlike himself,

while still remaining the same man.”

Postscript

I visited Shanghai again in the spring of 1982. More cars were then seen on the main streets which were jammed with swamps of bicycles one year ago. Corner stores began to appear, some opening 24 hours. University life became normal again, rid of demands for class struggle. Professor Hu asked me to speak to the administrators and professors of East China Normal University. Afterwards, he also asked me if I could help his student to study in Canada for one year, so he could complete his Ph.D. degree in Psychology. To study abroad had then become a requirement for doctoral studies in a new policy.

“My student, Junchen, came from a workers class, but very intelligent and studious.” Professor Hu told me, “He studied biology as soon as the universities reopened, and he is now studying Psychology with me.” He also informed me that the government would pay for the student’s airfare but nothing else. It struck me as a weird policy. But I was very happy that Psychology was vindicated and officially accepted. I promised to help.

Back in Toronto, I spoke with my Dean and asked for his assistance. I suggested that I would donate $4000 to the university for the specific purpose of a scholarship for Junchen. He would be accepted as a visiting scholar so he would pay no fees, but would be allowed to participate in all activities in our Faculty, including attending classes of his choice. The suggestion was accepted. In the fall, Junchen came and lived with me. He went back to Shanghai the following year, and he was conferred the PhD degree in Psychology in the spring of 1985, the first in the People’s Republic of China. He is now the foremost expert in human resources development in China, a full professor of a key university teaching psychology and management programs offered jointly with Harvard University.

Regrettably, Professor Hu died in October 1989. He was riding at the back of a fully packed bus when he fell gasping for air. The bus would not stop, and nobody moved to let him out. The people in Shanghai is now consumed by a new ideology, that of getting rich and efficient, forgetting to care.