Introduction

I wrote China Meets the World, a series of eight articles on the occasion of the 30th Anniversary of China’s opening policy. They had documented the historic and individual events surrounding the change from a closed China to her wish to connect with the world. The first article indicated the immense difficulty of educating the change pioneers to adjust to a world of diverse possibilities, when they were trained to believe that everything must be measured by a dichotomized scale of rights and wrongs.

I am writing this series of China Meets Herself now, three years later, to mark out some of the behaviors and questions that have emerged among the different generations of people of urban China today. They reflect their response to the huge change that is taking place, as China attempts to live with herself, and to play a pivotal role in the one-world reality.

Laoze says: He who knows others is informed; he who knows himself is wise. He who defeats others is powerful: he who conquers himself is mighty. He who knows satisfaction is rich….he who loses not his place will live long. In my experience, the Chinese people have always lived by traditional wisdom. Sixty years of communist education and rule had not changed that. The events narrated in this series will show some aspects of this cultural continuity.

A Family Saga in 70 Years

The old lady is gone, at 99, quietly, leaving a disquieting past. Her life reflects the conditions of China in a century and a half.

She was my Espouse Mother (契媽). The relationship began seventy years ago in Hong Kong, when her oldest son Kam Chong (錦松) and I were kindergarten chumps for three months, before the Japanese attacked the colony. Rumours had preceded the immanent attack for more than a year. People were stocking up food and firewood, as well as getting ready to leave the place. We kids lived with these activities.

One day, during recess, Kam Chong and I pledged that we would be good friends forever, that even separated by war, we would find each other again. That very day I visited his home and met his mother. Two days later, our two mothers got together, and decided that Kam Chong’s mother would take me as her espouse son so the two of us would be espouse brothers.

The Japanese came at Christmas that year. They occupied Hong Kong for three years and eight months. Many people died, or left for China. A small number survived the ordeal. Hong Kong was handed back to the British represented by a Governor whisked from the Japanese prison. Two other representatives were also present in the ceremony, one sent by the Kuomintang, the other sent by the Chinese Communist.

China plunged into a bitter civil war after Japan’s surrender. When the Communist government reigned over the mainland with the establishment of The People’s Republic in 1949, floods of people rushed into the colony in the succeeding years. Arriving from all parts of China, these people eventually made Hong Kong a thriving international city.

I came back to escape a confused and lawless rural China in the summer of 1948. I attended school, taught school, and left for Canada for graduate studies in 1958, completing my PhD in 1960. I returned to live in Hong Kong thirty years later, after taking early-retirement from teaching at the University of Toronto.

I received a surprised telephone call one day in 1995, from Kam Chong. “You are my famous old brother,” he yelled in excitement, “I have been watching your name in the newspapers for months and am sure that is you. I congratulate you wholeheartedly for your appointment as a Hong Kong Advisor.”

We got together. We had each gone through our own ways for half a century, experiencing wars, calamities, and monumental changes. Here are the circumstances in his family. His mother had given birth to six children, three boys and three girls, including him. They had all graduated from famous universities, in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Harbin, and served Mao’s China. Only the youngest brother, Richard was lucky enough to get out of China in his teens. He is now an astronomer from Harvard, and his two sons, the third generation, are lawyers. They are all American citizens. “I am the only non-grad, barely finished high school.” Kam Chong, who now often called himself David said flatly, “When my parents and the family went back to live in Communist China in 1950, I chose to stay in Hong Kong alone. My father had a small factory in Guangzhou, and he was told by the new government that he was welcome to run his factory to help build the new economy. He would be regarded a patriot doing so.

“Then, disaster came. Father was branded an exploitive capitalist in 1952. His factory was seized and he was imprisoned. He died in captivity three years later, leaving my mother to look after the family, with me helping what little I could.”

With the statement “My Mom is a genius, with unsurpassed ingenuity”, David gave an account, in many hours, of how, in half a century of tumultuous change, the lady survived the political and economic changes to bring up a fine family. In the end, she had left an estate of three flats in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Moreover, she had succeeded to bring or sent three of her children and a grandson out of China, seizing every opportunity when there was a policy change.

She herself had weathered the injustice and tortures of the Cultural Revolution, and escaped China for Hong Kong in 1974. Then, she returned to live in Shanghai in 1996, to be near Wuxi, her birth place, because the cost of living was much lower. She lived in a comfortable flat with a maid, managed by her daughter Xi Yin (惜茵), whose husband, a member of the Communist Party, teaches at a key university. Xi Yin is also a professor. Retired now, she is a member of Zigong Tong (致公堂), the officially recognized Organization of Believers of Democracy.

“But,” David said in a weeping voice, “in the end, Mom died in hospital, alone.”

David had his personal struggles too, following the ups and downs of Hong Kong’s economy. He is now a well-to-do business man, the proprietor of a local advertising firm, specializing in the sales of unipoles on the highway rams of three major airports in China. He and his wife have two grown-up children, both professionals. They and their families live in Toronto.

The Funeral

All the six brothers and sisters and their spouses gathered in Shanghai for the funeral. They got in within four days, from Los Angeles, Toronto, Hong Kong and Zhuhai. There were also five grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Xi Yin had efficiently made all the arrangements. Her talent for organizing people and events was well known, even in her high school days. She would have been admitted to the Communist Party, had her “class status” not been marred by the fact that her father was an exploitive capitalist. To stay ahead, she married a party member and now, she has become a “democratic personality”.

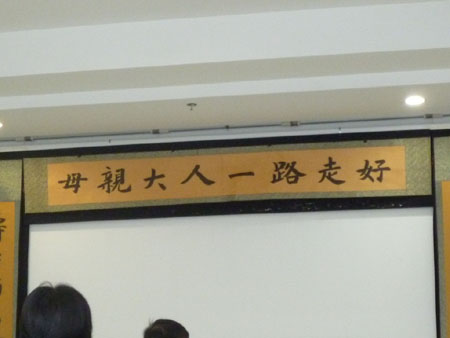

The funeral was held at the Municipal Funeral Home, the only one in Shanghai, a city of seventeen million inhabitants. It was a grand open structure, made up of parks, waiting areas, cremation facilitates, and about 50 halls for funeral rites. Every hall bears a traditional name, to wish the dead well on the way west, toward the ultimate happy place in the universe, a Buddhist belief. Ours was called the Hall of Eternal Peace (永安堂).

The funeral was held at the Municipal Funeral Home, the only one in Shanghai, a city of seventeen million inhabitants. It was a grand open structure, made up of parks, waiting areas, cremation facilitates, and about 50 halls for funeral rites. Every hall bears a traditional name, to wish the dead well on the way west, toward the ultimate happy place in the universe, a Buddhist belief. Ours was called the Hall of Eternal Peace (永安堂).

The administration was most efficient. Each mourning family was allowed to occupy a rented hall for one hour. Thus, by a quick count, the Home could process a total of about 400 cases per day. My espouse mother’s hall was at the end of the row on the ground floor. On the way to it, I saw other larger halls decorated with towers of fresh flowers and laces. These decorations and their removal could not be done within the hour limit. There must be classes of halls and rental conditions to satisfy the needs of mourners with special status.

By her wisdom, Xi Yin had kept our ceremony simple, allowing only family members to attend. The rites master briefed us on what to do. He would wheel in the coffin for us to pay our last respects. We would then have twenty minutes to put flowers and gold and silver joss notes around mother’s dead body, so she would have money to spend in the under world. The pall-bearers would then come in to cover the coffin and take it away for cremation. We would follow him on foot to the other side of the park to cross the “fire bridge”, under which our mother was being cremated.

As it happened the process worked like clockwork, completed within an hour to avail the hall for the next group. Parting is always difficult, especially with the dead, because it is final. David’s brothers and sisters were educated in the communist schools which taught them to believe that a person’s death is the termination of a physical body, material in nature. It is a scientific fact and nothing more. Yet, they wailed and lamented when the coffin was covered to be taken away.

Many questions and thoughts crossed my mind as I participated in the process.

The first was how badly the communists had failed in their effort to hail the collective character of human nature, eliminating the value of the individual person. The second was their total failure in decimating the child-parent relationship in favour of an unquestioning loyalty to “The Party”. I remember well how, right after 1949, children were taught to repeatedly sing: “Don’t love Papa and Mama, love only your country”. Today’s schools do not teach such songs any more. But, anyone who dares to say, that loving one’s family should take priority over loving one’s motherland, will be seen as unprogressive.

A third question is of a larger historic proportion. What egoistic forces had empowered the so called national heroes, like Lu Shun, Hu Shih and Mao Zedong, to urge generations of young people to refute and destroy the age-old Chinese culture and tradition? Lu Shun attempted to rid the practice of Chinese medicine and theater from the land. Hu propagated that we should resolutely replace our culture with the American culture, because the latter was superior by far. I doubt if he knew enough English to understand America. Mao went much further. He closed all schools for ten years to urge an entire generation of students to “struggle” against their parents and teachers, and to destroy their cultural heritage, in the name of perpetual class struggle. Fortunately, they had failed.

“How did the funeral home survive the Cultural Revolution when everything considered to be traditional must be destroyed?” I stole a second to ask the rites master.

“How would I know? I was not even born then.” He gave me a strange look as he answered dryly. I guess he might be questioning why I was interested in such ancient matters.

The Feast and Gripes

We headed for lunch at the Little South Country (小南國), a restaurant famed for Shanghainese cuisine. With the heavy task off hands and minds, the brothers and sisters called for their most favorite dishes to celebrate. Mother’s death had been expected for years. Whatever sorrow there was had dissipated almost mechanically as people left the funeral home. The only remaining task to be carried out was the collecting of the ashes two days later. It would take that long for the ashes to cool because of the super-intense heat employed in burning down the flesh and bones.

Eating reflects the class difference of people in Shanghai today, as in almost any city in China. A commoner can have a hefty and delicious breakfast of two or three niceties and a bowl of soy-bean milk for 3 RMB. The rich pays 260 RMB for a buffet breakfast at a five-star hotel. I had my eyes opened at lunch when someone ordered smelly tofu, at 186 RMB per dish. He could have the same thing at the market at 6 RMB, complimented by a larger variety of authentic sauces.

For Xi Yin’s husband, Wei Min (為民), the Communist Party member who still has a position at the university in retirement, a meal must include sharks-fin soup and lobster to match. He had learned about this from meeting with the big donors to the university from Hong Kong. In his dialectic-deductive mind, he had concluded that a meal is not the best unless it is most expensive in price. In private though, his favorite food is still the folksy native food he appreciated while growing up, consisting of small shrimps, preserved snails, and lots of rice. He is an orphan raised by his uncle who was a dock worker. He joined the Communist Party in his high school days. He is politically very astute, moving where the wind brows. In the blurry political climate of China today, he and his wife have all the political angles covered. They are also financially rich, owning six flats with profits from property speculation.

The group of brothers and sisters and spouses gathered in their mother’s flat after lunch. There was much to do, including going over the Will, reviewing past life with boxes of photographs, and singing revolutionary songs to mock their own foolishness when they were young.

Photographs are vivid and true records of history. The black and white photos go back to the parents of the matriarch in Wuxi. It was an affable family in business, according to the hand-written autobiography that mother had kept in a jewelry box. She was the first girl to attend a modern school ran by an American Presbyterian Mission. When she finished elementary school at fourteen years old, China was divided by the warlords and facing foreign invasion. She got married two years later and lived with her husband in Guangzhou and Hong Kong. The rest of her life was intertwined with the fate of China, as she went through war after war, then ideological struggles, until her husband died a political victim.

One photograph was cherished by everyone. It was a family portrait of eight, with the youngest son, Richard, a baby in mother’s lap. Taken in Hong Kong just before they moved back to Guangzhou, the picture in hand-painted colours, showed a wholesome and healthy family, with everyone looking handsome and intelligent. Then, thunder struck. With papa gone and mama a widow, the rest of the hundreds of photographs are of individuals and new families, taken at various times and in different places around the globe.

Before father died he requested mother to watch out for opportunities to take the children out of China. Richard was the first priority. The rest would depend on circumstances. He had left one flat in Hong Kong, and the rent would be enough to send Richard to study abroad. As things turned out, the children were all high achievers in schools and universities. Mum seized an opportunity to bribe an official to allow Richard out to Hong Kong, thus to fulfill her husband’s last wish. After finishing high school he won a scholarship to attend Harvard. The other siblings all achieved professions from key universities, in irrigation engineering, finance-economics, climatology, and chemistry. They and their spouses had all been assigned jobs in remote areas to serve China’s technological needs.

The singing of revolutionary songs soon turned into an all-out complaining session.

“We’ve been cheated by Chairman Mao and his system to be sheer slaves!” began the engineer, “To serve the people was a dirty lie. I spent three decades of my youthful life to design dams for African countries. But I’ve never set foot even once on African soil, simply because my father was branded an exploitive capitalist. Then, I could only work as a draft technician in Hong Kong to stay alive, after I got out of China in 1980. What a big joke!”

“I had my life pawned to ‘the call for watching the atmospheric changes’ in Tien Shan near the Kyrgyzstan border, so our country could have accurate weather reports for good agriculture. My kids had no school to go to. We braved the harsh living conditions for years, feeling heroic that we were serving our motherland. Our illusions cracked like hard clay, when we found that such movements as the Big Leap Forward had turned agricultural production into mere political power struggle”, griped the climatologist. “And now, my son could only work as a fast-food cook in Hong Kong.”

“What fools we were looking back,” the chemist grumbled, “a good part of my job was to improve dyes to make cloths bright red, to be made into flags and banners propagating the slogan that ‘Tomorrow will be better’. Little did we know that the facts were speaking against the claim, because we did not have enough to eat towards the end of the Mao Era. Tens of millions of youths have been brain-washed to believe that Chairman Mao was their savior and their future. He was just a liar.”

Wei Min joined in, when the complaints became bitterer and targeted on Chairman Mao. He always likes to be the cool one to sum things up. “We all know the rules in the biological world, as the great Darwin had it, survival of the fittest” he said, casting his eyes around the room to make sure people were listening.

“You make the best of things in life, no matter the situation. Communism is an import. Our Chairman Mao made a wise twist of it to fit the great revolution which saved the mass proletariat in our motherland. I often reflect on my own life. I would be a wretched dock worker if it were not for the revolution” he continued.

People in the room yelled for him to stop, ridiculed him for being a dirty capitalist with the false identity of a party member. They demanded that he dropped his hypocrisy and be a true gentleman. Even his wife asked him to be quiet.

“Listen,” he persisted disdainfully, “No one is saying that communism is good for China. But what do you have to replace it? We all know what we had gone through. But it was not our Chairman who did the damage. It was the people who were liberated. And now our Party has set the policy for opening; and here we are, speaking freely and eating great food. I was in Silicone valley to visit my daughter last month. She was educated here in Shanghai before going to study abroad. She and her partners are on the cutting edge of high and new technological inventions. But I saw Americans there working busily like dogs. Many are seeing psychiatrists every week. The blacks do the most menial jobs. It is not Heaven there. I suggest we look ahead, instead of bemoaning past sufferings. We are in our seventies now and deserve a good life. I suggest we go to have a good dinner.”

Legacy Continuation

Kam Chong was the Executer designated by his mother in her Will. As the eldest son and staying in Hong Kong all these past years, he had been mother’s pillar as she went through the vicissitudes of change to take care of the family.

“I have great news for all of you,” he announced after calming down the moaning group, “Our beloved and great mother has willed that her estate will be divided into six equal parts, each for her six children. She had done well in every respect, as mother and money manager, despite the many odds of her time. I know we are all grateful for what she had done for each of us. Here, as you can see from the copies of her Will and the rough estimate statement of the value of her estate that I am placing in your hands, each of us will be getting about three million Hong Kong dollars, when the properties are liquidated.”

The group was jubilant. The size of the estate was unexpected. Some were ecstatic. They had not seen so much money any time in their lives. Others wept in disbelief and gratitude. They felt ashamed that they had not cared for their mother often enough.

“I also like to tell you,” Kam Chong continued, “I shall use my share to set up a fund to pay for all the expenses for mother’s funeral. All your airfares, hotel expenses and foods will be paid by this fund.”

The group cheered like happy children.

“I urge you to read mother’s autobiography. It is very well written, containing the family trees of her maiden family and our family, as well as her wishes. When father died she took great pains to have his ashes taken home, much against the rules. Months later, she and I had them smuggled out into Hong Kong, where we had them placed in a purchased cubicle at a Buddhist temple. It is her wish that her ashes be placed beside those of father. You may join me to do this later.

“Meanwhile, we will attend a Buddhist blessing rite to calm her soul, and to guide her spirit to travel to the ultimate happy place in the Western Hemisphere, where she will rest in peace forever. Mother deserves it. Her life had been spent in all the conflicts and problems of our motherland. We must recognize her ingenuity and love. She had overcome all the difficulties and sorrows to make us what we are. Xi Yin had made the arrangements at the Jing An Temple (靜安寺) and she will give you the details later. I must take this opportunity to openly thank Xi Yin for looking after mother here in Shanghai during the past sixteen years. I suggest each of you to thank her in your own ways.

“The last wish of mother is to see us happy, thriving and loving one another, wherever we may be. Although born in rural China a century ago, mother has kept herself on top of a swiftly changing world. She had listed in our family tree all members born to our families up to 2007, with information given to her. She had expressed great satisfaction that there are so many of us, living in so many countries, and thriving in so many ways.

“She wants us to keep up with the kinship, and continue to remember our roots and legacy. I suggest we make our best effort to fulfill her wishes. I suggest that, in addition to keeping close communication with one another, we have a family reunion once every year or two years, bringing as many family members as possible. May be we could chatter half a cruise to the Mediterranean. The fund that I am setting up will finance it. I believe this is the best way to remember our dear mother.”

Feasting Shanghai Style

The troop of family members, twenty-seven in number including me and my wife, then headed for dinner. Xi Yin had already made the advance booking at this luxurious restaurant set in the old residence of the famous Kuomintang General Bai Chong Xi (白崇禧公館). She and Wei Min are regulars of all the plush restaurants here in Shanghai.

The troop of family members, twenty-seven in number including me and my wife, then headed for dinner. Xi Yin had already made the advance booking at this luxurious restaurant set in the old residence of the famous Kuomintang General Bai Chong Xi (白崇禧公館). She and Wei Min are regulars of all the plush restaurants here in Shanghai.

The residence is in an estate of wooded fences, ponds and flower beds wounded by meandering paths. The main building is three stories high, covering the width of a city block. It is now used for diners and friends who are members of exclusive clubs. Fifty yards from it is a larger glass structure of the same height, semi-circular and grand, decorated with chandeliers. It caters to the general public. A system of doorman would make sure that no one enters the wrong door.

Our group occupied two large adjacent rooms. The mood is cheerful and at ease, as the gripes and moaning in the afternoon had dissipated years of grievance and injustice. Knowledge of the inheritance had also set people’s spirit high. This beautiful dinning palace certainly adds to a mood of gaiety.

Chinese tradition has a practice that when a person dies of very old age, her descendants should be joyful rather than sad. If the diseased is rich and respected, feasts would be offered to anyone who comes to pay respect. The rice bowl and chopsticks used at such free feasts would be gifts for the guests, carrying the blessings of the dead. Wei Min told the group about this tradition to urge everyone to order his/her favorite dishes. He had learned about it recently while visiting Taiwan.

Watching this congenial group enjoying the fine food and the kinship, I observed that three generations are present. The most unusual attendee is a pair of newly-weds who have not met their great grandmother while she was alive. The man, Angus Hui, is the elder son of David’s daughter who married a Chinese-Canadian in Montreal. He met his future wife, Joyce, a Beijing girl, when they were attending Osgood-HallLawSchool. They were married after they crossed their bars. They had come to work in Beijing two months before this event. Joyce is an only child and her parents and grand parents wanted her to be near them.

I whispered to David: “You are right indeed that our mother a most perceptive woman of her time. She knew and accepted that her descendents would not be limited to living in China. She had wished that they be happy, united and thriving wherever they might be. Little did she expect that even those born and educated in foreign countries would return to China to work and may be to settle. She would be most satisfied if she was here to see this new couple being a part of her lineal continuity.”

He took my hand, held it firmly, and said: “You are indeed my good brother: you know mother well.”