Chinese and Foreign Sages and Poets Look at Stages of Life

孔子 (551– 479 BC):《論語 · 為政第二》

子曰:"吾,十有五,而志于學,三十而立,四十而不惑,五十而知天命,六十而耳順,七十而從心所欲,不踰矩。"

少年聽雨歌樓上

紅燭昏羅帳

壯年聽雨客舟中

江闊雲低斷雁叫西風

而今聽雨僧廬下

鬢已星星也

悲歡離合總無情

一任階前點滴到天明

王國維 (1877-1927):《人間詞話》第二十六條, 說人生三境界

“古今之成大事業、大學問者,必經過三種之境界。

‘昨夜西風凋碧樹,獨上高樓,望盡天涯路。’此第一境也。

‘衣帶漸寬終不悔,為伊消得人憔悴。’此第二境也。

‘眾裏尋他千百度,回頭驀見,那人正在燈火闌珊處。’此第三境也。”

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592, French): Of Age (in Essays)

… And therefore my opinion is, that when once forty years we should consider it as an age to which very few arrive. For seeing that men do not usually proceed so far, it is a sign that we are pretty well advanced; and since we have exceeded the ordinary bounds, which is the just measure of life, we ought not to expect to go much further; having escaped so many precipices of death, whereinto we have seen so many other men fall, we should acknowledge that so extraordinary a fortune as that which has hitherto rescued us from those eminent perils, and kept us alive beyond the ordinary term of living, is not like to continue long.

'Tis a fault in our very laws to maintain this error: these say that a man is not capable of managing his own estate till he be five-and-twenty years old, whereas he will have much ado to manage his life so long. Augustus cut off five years from the ancient Roman standard, and declared that thirty years old was sufficient for a judge. Servius Tullius superseded the knights of above seven-and-forty years of age from the fatigues of war; Augustus dismissed them at forty-five; though methinks it seems a little unreasonable that men should be sent to the fireside till five-and-fifty or sixty years of age. I should be of opinion that our vocation and employment should be as far as possible extended for the public good: I find the fault on the other side, that they do not employ us early enough. This emperor was arbiter of the whole world at nineteen, and yet would have a man to be thirty before he could be fit to determine a dispute about a gutter.

For my part, I believe our souls are adult at twenty as much as they are ever like to be, and as capable then as ever. A soul that has not by that time given evident earnest of its force and virtue will never after come to proof. The natural qualities and virtues produce what they have of vigorous and fine, within that term or never,

"Si l'espine rion picque quand nai,

A pene que picque jamai,"

["If the thorn does not prick at its birth,

'twill hardly ever prick at all."]

as they say in Dauphin.

Of all the great human actions I ever heard or read of, of what sort soever, I have observed, both in former ages and our own, more were performed before the age of thirty than after; and this ofttimes in the very lives of the same men. May I not confidently instance in those of Hannibal and his great rival Scipio? The better half of their lives they lived upon the glory they had acquired in their youth; great men after, 'tis true, in comparison of others; but by no means in comparison of themselves. As to my own particular, I do certainly believe that since that age, both my understanding and my constitution have rather decayed than improved, and retired rather than advanced. 'Tis possible, that with those who make the best use of their time, knowledge and experience may increase with their years; but vivacity, promptitude, steadiness, and other pieces of us, of much greater importance, and much more essentially our own, languish and decay:

"Ubi jam validis quassatum est viribus aevi

Corpus, et obtusis ceciderunt viribus artus,

Claudicat ingenium, delirat linguaque, mensque."

["When once the body is shaken by the violence of time,

blood and vigour ebbing away, the judgment halts,

the tongue and the mind dote."--Lucretius, iii. 452.]

Sometimes the body first submits to age, sometimes the mind; and I have seen enough who have got a weakness in their brains before either in their legs or stomach; and by how much the more it is a disease of no great pain to the sufferer, and of obscure symptoms, so much greater is the danger. For this reason it is that I complain of our laws, not that they keep us too long to our work, but that they set us to work too late. For the frailty of life considered, and to how many ordinary and natural rocks it is exposed, one ought not to give up so large a portion of it to childhood, idleness, and apprenticeship.

(I have put his key ages in bold. – FY)

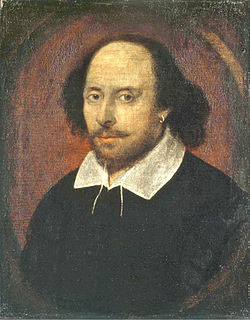

William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616, English): All the World's a Stage (in As You Like It)

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress' eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon's mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

John Keats (1795-1821, English): The Human Seasons

Four Seasons fill the measure of the year;

There are four seasons in the mind of man:

He has his lusty Spring, when fancy clear

Takes in all beauty with an easy span:

He has his Summer, when luxuriously

Spring's honied cud of youthful thought he loves

To ruminate, and by such dreaming high

Is nearest unto heaven: quiet coves

His soul has in its Autumn, when his wings

He furleth close; contented so to look

On mists in idleness—to let fair things

Pass by unheeded as a threshold brook.

He has his Winter too of pale misfeature,

Or else he would forego his mortal nature.